|

By Tom Carter

Staff Writer

Fast-paced, predominantly hard-sell and

programmed to lull the fickle audience into a kind of electronic euphoria.

That's AM "rock" radio in Lexington at WVLK and WLAP, where giving the

audience what it wants means playing more of the same hits more often.

Fast pace - the knack of fusing a commercial message and a rock hit into one

indistinguishable spiel - has been well-mastered here.

The hard-sell isn't totally dominant. Lexington is still enough of a country

town to harbor a few advertisers who won't tolerate it.

But listeners get more records per day here than in bigger markets, but not

a whole lot more.

At WVLK, approximately 35-40 contemporary records are played daily - in

addition to three "oldie goldie" hits per hour -- and at WLAP -- where

oldies are played one-to-one with current hits -- the record survey is 30

contemporaries (each played once every two hours) and 10 played three to

four times a day.

The city's third AM station, WBLG, is programming generally for "easy

listening" and is not geared to the same audience as the other two stations.

The multiple replays of the same stuff may sound like saturation to someone

who doesn't know Billy Preston from Barry White, but in the bigger market

stations there's even less variety.

More and more stations have moved into the rock music market in recent

years. The competition is fierce in bigger cities where stations play only

15 to 20 different top hits a day to keep the audience's attention.

But this has put the record industry into the position of releasing less

records because they get so little free air play anymore for the bulk of

them.

"Oldie" Problem

"Oldie goldies" are a big part of the problem.

The other is the teen-age (or younger) record buyer whose short-term,

ever-changing music preferences make the industry the maddening business it

has become.

The oldies are a broadcasting phenomenon. Old can mean a record from a few

months to several years out of its prime interest period, but most often

means records of the 1960s and late 1950s.

Herb Kent, program director at WLAP, says that he hasn't noticed any decline

in record production in recent years.

And both he and Jim Jordan, program director at WVLK, indicated that the new

record market is littered with losers.

Jim Allison, station manager at WLAP, doubted that any more new releases

would be played if the old records were not enjoying a revival.

"You'd probably only hear the new ones a little more frequently," he said.

But determining how often something should be played is decided after

someone determines what should be played.

At both WVLK and WLAP, the program and music directors have this chore and

disc jockeys aren't at liberty to deviate from it.

Both station's personnel review the music lists weekday. The barometers for

deciding what records should be played are:

- What are the stations in the bigger

markets play? Playing copycat isn't a bad risk when the copy is a

high-powered station like WABC in New York. Local stations get weekly

lists on what everybody is doing.

- What are people buying locally and

nationwide?

Both stations canvas record stores in

Lexington to see who is buying records or requesting records the stores

don't have.

Requests Count

Outside influences often affect the local

market if requests are made for a record many people have heard either on

other stations or while visiting or travelling out of town. Spotting a

trend-setter gives a local station an edge.

The nationwide sales figures come through trade magazines like Billboard and

Cash Box which keep track of current and promising hits as well as bad bets.

- Call-ins to the radio station. WVLK has

a request line with an automatic recorder. It is checked twice and hour.

"If people take the time to call in a

request, they obviously like it," Jordan said, adding that the day and night

call-ins generally reflect the tastes of the different audience and the

station changes its oldies to reflect it.

Admittedly, there is not much variety in music programming on rock stations

in markets the size of Lexington.

Variety usually happens in two other locations:

- Small towns with only one radio station

where programming variety isn't hampered by competition.

- In cities the size of Chicago, where

variety doesn't come from the individual stations, but among them.

Jim Allison, manager of WLAP, said a

station's goal is to get the biggest "share" of the market. In Chicago, the

classical, jazz or talk-show format share could be as large as the entire

Lexington area listening audience.

But in most cases, the rock audience is the best target for advertisers and

even in the biggest cities where stations are vying for it.

With the stations so concerned about giving a lot of time to the national

hits, it would seem discouraging to local talent which looks to the local

radio stations for promotion of the products. It is.

"We Listen…"

"We listen to them" comments Kent, "but we

can usually tell they're not going to be anything. I can usually listen to a

record and tell if it has it or not. Lexington is not a market for big

records."

Allison added, "It's a risk to play an unfamiliar record. Our people are

close enough to the business to be pretty sure of something before they play

it."

Jordan admitted that most local records can't compare technically with the

high-styled product from the big studios, but said, "We can give play to new

artists and hope that we can 'break' the record. We're a little luckier

because we're not in a major market."

Behind all this clamor to play the best of the least the most often is

ratings. The most popular stations can charge the highest advertising rates.

Besides, being number one is the point of doing anything with a commercial

bent to it.

The results of the annual survey of the local radio market will be out in

approximately two weeks. Number one -- WVLK is the apparent market leader --

will no doubt be vocal about it.

Figuring out who is number two, three, four, etc., will be another matter.

|

|

By Tananarive Due

Herald-Leader staff writer

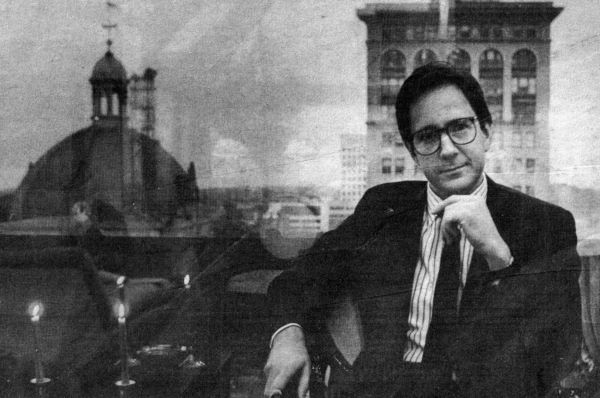

Paul

Hughes, president of Hughes Media Cos. of Lexington, describes himself as a

"multimedia enthusiast" but says that radio will always be his first love. Paul

Hughes, president of Hughes Media Cos. of Lexington, describes himself as a

"multimedia enthusiast" but says that radio will always be his first love.

Hughes has dreamed of owning his own radio

station since he was 16 years old. On May 27, that dream came true when his

first station, WMAK in London, signed on the air. He hopes a second station

will be on the air by next spring.

"It was a childhood dream. Once it's in your

blood, it never goes out," Hughes said, recalling that when he was growing up

in Baltimore, he built a recording studio in his bedroom so he could tape a

high school radio show.

Before fulfilling that youthful dream, however, Hughes tried his hand at radio

and television programming, broadcasting and production; advertising; and

graphics. He also had a go at journalism.

Hughes Media Cos., which began as an advertising agency operated out of the

back seat of a Chevy, today is parent company to an advertising agency, a

graphics studio, and a separate partnership formed to build and operate radio

stations.

The company is celebrating its 10-year anniversary. It has grown from

employing three people to employing 13 people. The company offices recently

were moved to a penthouse in downtown Lexington, where Hughes has a sprawling

view of the city from his office windows.

Hughes got his start in the media at age 19, when he joined the Air Force. A

recruiter had sold him on joining by telling him he could get some experience

in journalism. Instead, Hughes was sent to Mississippi and told that he would

be trained as an air traffic controller.

"It's the same story you always hear -- my recruiter lied to me," Hughes said.

But he was undaunted. While he was being trained as a controller, he got an

unpaid air shift at a 50-waft bootleg radio station that had been built in the

barracks.

Although the station operated without licensing it was shielded from Federal

Communications Commission regulations because it was on a military base.

But the Air Force, too, frowned upon its operation. Hughes, seeking Air Force

approval, said he approached superiors in Texas with an idea for developing

carrier current radio stations on other bases. Carrier current stations use a

type of closed-circuit transmission.

"They thought it was an intriguing idea, so I was sent to design some

blueprints," Hughes said.

That experience merely whetted Hughes' desire to work at a real station, and

he took a night job on a nearby Biloxi operation.

He also wrote for the Biloxi newspaper and worked some at a local TV station.

Meanwhile, he also wrote for the base newsletter.

At a glance

Paul J. Hughes III,

president, Hughes Media Cos.

Birthplace: Louisville; Sept. 27, 1949.

Education: University of Kentucky, telecommunications,

1973-76.

Family: Divorced.

Career: Air Force, 1969-1973; WTVQ Television, 1973-74: WEKY

(Richmond), 1974-75; WBLG-AM/WKQQ, commercial producers, staff

announcer, 1975-76; WVLK, commercial producer, 1976-77; Hughes Media,

1977-present.

Quotation: "Go to a small operation and get some real working

experience. Try to define specifically what you want and go do it.

That's how I feel I've benefited....A lot of schools don't prepare

people for the realities that will be out there."

|

After leaving the Air Force in 1973, Hughes

came to Lexington to study telecommunications at the University of Kentucky.

He worked at the newborn WKQQ, then took a job with WVLK. By day, he was Paul

J. Hughes to adult listeners, then "Pablo" to the younger set at night.

But that never seemed to be enough.

"I was always bored on the air,' Hughes said. That boredom sometimes led to

run-ins with managers because Hughes liked to use plays on words and

occassionally told jokes his managers though were unacceptable.

While still working full time at WVLK and attending classes at UK, he and two

friends decided to start an advertising agency. One of the three had a friend

at a local Radio Shack store, and they made a pitch for its advertising.

Radio Shack hired them. Hughes said the advertising campaign was "very

primitive," but it was a small beginning. Their "offices" were the back seat

of Hughes' Chevy.

Concerned about a conflict of interest, Hughes quit his position at WVLK and

moved into a small office with his then-partner Skip Olson and a secretary.

"We were very determined, and perseverance and midnight oil kept us rolling,"

Hughes said.

Hughes and Olson bought Creative Concepts, a failing graphics studio in their

building. Olson now is director of Creative Concepts.

"I'm in awe of the fact that he's held everything together," Olson said of

Hughes: "He's got a determination and he's always got a real desire to do the

best possible job. It's everything to him"

Hughes Media has handled Dawahare's clothing stores' account for 7.5 years.

Hughes Media wrote the "No One Does It Better" slogan, for which Hughes does

the voice-overs.

His company's growth has its price, Hughes said. He used to have a role in

every aspect of this company, from writing to shooting the videotape to

voice-overs. Now, "I'm involved less and less with the creative side of the

agency," he said.

Paul Hughes, president of Hughes Media Cos., has

a good view of downtown Lexington from his offices.

Despite his success as a businessman, "my

real love has been radio programming, the marketing approach the station uses

on the air to secure listeners," Hughes said.

In 1981, he began to think about owning his own station. He met his partner,

Kevin Moore, through Moore's work as sales manager for a statewide radio

station network, the Kentucky Network.

Hughes and Moore found they had a mutual interest in radio and spent two years

researching locations to determine where a new station might work.

They formed Hughes-Moore Associates Broadcasting Co. in 1983 and obtained a

permit to operate an AM station in Midway and began building a tower on the

Midway College campus.

That decision was "Biting off more than I chew, as usual," Hughes said.

The school administration changed its position about the tower, so Hughes and

Moore had to find a new site and repeat the application process. They ended up

spending $30,000 more than they had planned.

Meanwhile, their attorney in Washington , D.C., told them about an AM radio

station in London that had gone off the air.

"We were a little leery of it," Hughes said. "We looked into Laurel County and

looked at...the community and population to determine if the station could do

well."

They bought the station's equipment and license, and they were in business.

"It's twice as hard as you might think it is," Moore said. "It's quite an

investment."

They picked an oldies format, primarily songs from the '50s, '60s and '70s.

Many of the records are from Hughes' personal collection, he said.

They chose the call letters WMAK because they had belonged to a popular

Nashville station Moore had listened to while he was growing up there. And

they picked Sam Cornett, who once worked for the original WMAK in Nashville,

as the operations manager.

Cornett previously had worked with Hughes at a Richmond station.

"He seems to be consistent," Cornett said of Hughes. "Anybody who's consistent

in this business is going to be successful. … He would not be where he is if

he didn't have some method.

Cornett said that while the station is starting small, he expects to see it

grow.

"This is the first time I have worked for a

station that signs off at sunset," Cornett said. "The reason I'm here is I do

have long-term plans with this corporation. I believe in Paul."

Moore said he and Hughes are "interested in pursuing other properties,

primarily in Kentucky." The Midway station has been on the back burner because

of WMAK, but Moore said they hope it will be on the air by spring of 1987.

Moore said that he and Hughes make a good team. "I think we complement each

other because Paul is good with the on-air part of radio and I'm goad with

sales" Moore said. "It's got to sound good, and it's got to make money."

Hughes said it is difficult to measure WMAK's listenership for advertising

purposes. Stations in smaller markets do not get ratings in the same way that

larger ones do.

"Basically, you just convince the local merchants that you're doing the right

thing," he said.

He said that community activities his station has sponsored also give it

recognition. Promotional campaigns have included a Halloween dance, opening an

abandoned bank safe to find historical "treasures" his station had planted

inside, and mailing tickets with numbers to everyone in town.

"We believe that being very locally oriented is the key in our success there.

It's not just the music that makes the radio station."

If anyone knows what makes a radio station, Hughes does, his friends say.

"He probably works too doggone hard, to tell the truth," Moore said. "But he

knows the radio business very, very well. He knows Lexington media very well."

"His strength is his intuition and knowledge in the broadcast media," Olson,

at Creative Concepts, said. "I'd put him up against anyone in that area."

Hughes' perspective has changed in one significant way -- he has gone full

circle from breaking radio rules to making them.

As a manager, he recalls his own on-air antics and acknowledges that be would

now object to such tactics.

"The one thing I've learned in radio is that you have to stay within the local

community's good-taste definition," Hughes said. "A radio station walks a fine

line when it decides to do something off color or risqué.

"It's a matter of community awareness as an

owner. You have to follow the community instinct."

|

|

By Robert Keiser

Herald-Leader staff writer

It is 8 a.m. and Larry Holmes is short, pudgy

and white.

Most commuters listening to him on the radio as they inch towards jobs in

Lexington do not know that, though.

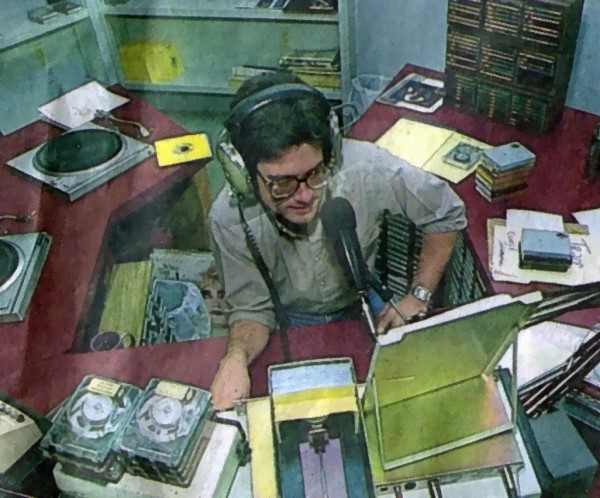

Only the coffee-powered morning crew at WKQQ-FM can see, through the window of

Studio B, that Holmes is really creative director Alex Bard.

Bard, whose hottest on-air impression is of Holmes, looks nothing like the

champion heavyweight. He has shoulder-length hair, a round, cherubic face and

a harder-hitting assortment of punch lines than punches.

But all that is fine, because this is radio: a never-never land where the

Eagles still play together, the 1960s live and people never look like they

should.

"You can sound like Robert Redford on the air and still look like Mickey

Rooney," said Karl Shannon, morning disc jockey at WVLK-FM.

Some listeners think it's the real Larry Holmes they hear on WKQQ, said Bard,

who also does a number of other voices for the station.

"If you have an imagination," he said, "you can create any kind of world you

want."

|

|

Dave "Kruser" Krusenklaus and Kelli Gates

Call letters:

WKQQ (98.1).

Target audience:

Ages 18 to 49 with emphasis on baby-boomer listeners from 25 to 40.

Typical artists

played: John Cougar Mellencamp, Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling

Stones.

Krusenklaus' favorite

artist: The Chuckwagon Gang.

Gates' favorite

artist: Zamphir, master of the pan flute.

Memorable on-air

moment: When a call-in show began to flop, Krusenklaus made a joke

about the phones not working. A General Telephone Co. repairman

promptly visited the studio to fix them.

Philosophy: "We

try to do a show in which we're just average Joes doing a radio show,"

Gates said.

|

The challenge, more than ever, is to capture

the listener's imagination in an increasingly competitive market, disc jockeys

say.

Most of that responsibility falls to the morning "drive-time" jocks, whose

shows -- all of which are live -- receive the most exposure.

"If you get a good morning team and it clicks, the rest of the day clicks,

too," said Barry Brown, general manager of WMGB-FM.

Kelli Gates, who shares the WKQQ control room each morning with Dave "Kruser"

Krusenklaus, said the "competition keeps us on our toes."

Stations in larger markets were faced with more competition after the Federal

Communications Commission deregulated radio in 1981, said Ralph Hacker,

general manager of WVLK-AM and -FM.

Until then, radio stations had been required to air some programming geared to

the town in which they were licensed to operate.

Since deregulation, stations licensed to smaller towns have been programming

to compete in larger markets nearby, Hacker said.

Central Kentucky communities with stations that compete in the Lexington

market include: Winchester (WFMI), Paris (WCOZ) and Georgetown (WMGB).

"Small towns gave up having radio stations," he said. "In every case, the

little stations were bought up by out-of-town folks and moved as close as they

could to the big city."

As a result, Lexington radio listeners have more choices than ever, Hacker

said. Bud Walters, co-owner of WFMI in Winchester, concedes that many of them

listen to at least two stations each day.

|

|

|

Indy Jones

Call letters:

WFMI-FM (100.1).

Target audience:

Ages 18 to 34 and women; teens.

Typical artists

played: Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson and Whitesnake:

Jones' favorite

artist: Paul McCartney.

Memorable on-air

moment: Jones, who prides himself on being quick on the uptake,

did not see the punch line coming when a man called live to suggest a

joke of the day. "Joe mamma," the man said. Jones, stunned, just

laughed. Most phone calls are taped now.

Philosophy:

"Music is the basis for our success.'"

|

Morning listeners, many of whom are facing

another day at work, search for a friend, said Frank Baker, one of the morning

"Breakfast Flakes" on WMGB-FM.

They also listen to the radio for escape, he said.

With music videos and increasingly explicit television and movies, radio

writers and personalities say their medium is the last frontier for the

imagination.

"People's imaginations are one of the neat parts of radio," said Krusenklaus,

the WKQQ disc jockey and operations manager.

Krusenklaus, 34, is a veteran disc jockey whose irreverence, quick wit and dry

brand of humor make him the David Letterman of Lexington radio.

In fact, an old issue of People magazine, its cover adorned with Letterman's

cigar-chewing face, is propped up on a table in Krusenklaus' office so that

anyone entering is greeted by them both: the wags of late night and early

morning.

Don't let Letterman's presence fool you, though. There in his office, "Kruser"

becomes Krusenklaus, the semiserious operations manager who smokes a lot of

cigarettes.

Only in the booth is he Kruser. But he clings to that identity once he walks

into the control room -- whether he's on the air or off.

"Could you grab me some coffee?" he asked Ron Mace, the station's right-hand

man.

They are in the booth, but they are not on the air.

"What do you drink, decaffeinated?" Mace asked.

"Yeah," Kruser said. "Black."

Then he smiled.

"You," he told Mace, "are like Lauren Tewes of 'The Love Boat': the perfect

cruise director."

Laughter filled the booth as the disc jockey started up Steely Dan's "Kid

Charlemagne."

"Like some people have genes for baldness or dark hair, sometimes I think I

have a performance gene in me," Krusenklaus said later.

"I'm kind of a private person….But I like to have a good time and be wild on

the air."

|

|

|

Jack Pattie

Call letters:

WVLK-AM (590).

Target audience:

Ages 25 to 54.

Typical artists

played: Bruce Springsteen, Carly Simon and Kenny Rogers.

Pattie's favorite

artist: Manhattan Transfer.

Memorable on-air

moment: Pattie doesn't care to talk about the most

memorable moment. Just say this: He wrote a letter of apology soon

afterward.

Philosophy: "If

you want to listen to music, you can always stick a tape in.

Full-service radio, like what we do, is better. Well, maybe not

better, but more solid."

|

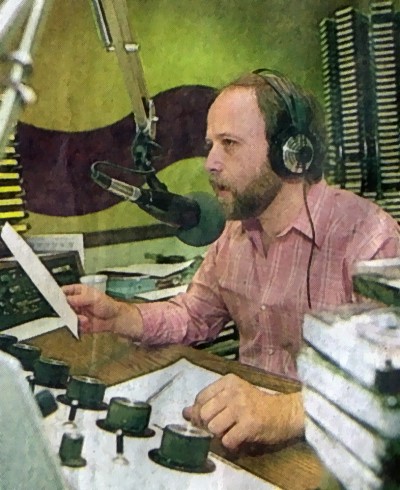

Jack Pattie, the 35-year-old veteran disc jockey who rides WVLK-AM's morning

show, said he also had "kind of a wild, crazy image" on the air.

"But I'm not," he said.

Pattie, who looks -- and sometimes acts -- something like a life-size

leprechaun, has attracted a loyal following with his fun-poking humor and

call-in show.

He has two young daughters, one of whom gets the credit for the idea behind

his whimsical ads on LexTran buses. The ads depict Pattie hanging on the side

of the bus, his tie whipping in the wind.

Yes, this is the same man who teaches Sunday school classes and works in his

family's jewelry store in downtown Lexington.

The disc jockey's life is not glamorous, said Gary Green, 34, morning man on

WLAP-FM.

"When I get off the air, I just like to go home and play with my gerbils and

not be bothered."

On the air, it's a different story.

As long-distance owners take more risks, stations are taking more callers,

sponsoring more contests and doing more special shows. Take WKQQ's Ms. Morning

Show pageant, for instance.

For fun and prizes, the contestants parade in front of judges, including

Baird's Holmes -- in bathrobes. Oh, yes -- and they answer questions such as,

"Lava lamps: passing fad or permanent part of American culture?"

"What they're looking for is someone who's able to take a little bit of

abuse," said Phyllis O'Dell, 41, who won the 1986 pageant.

"I like the morning show," she said. "It's a lot of fun."

At least two stations -- WLAP-FM and WMGB-FM -- have tried injecting more fun

into their morning shows just this year.

WLAP-FM, which abandoned automation in favor of live broadcasts in March, has

seen its once-faltering ratings rise dramatically since the change.

|

|

|

Pete Hamlett and Frank Baker

Call letters:

WMGB (103.1).

Target audience:

20 and up; women.

Typical artists

played: Steve Winwood and Whitney Houston.

Baker's favorite

artist: George Thorogood.

Hamlett' favorite

artist: Sting.

Memorable on-air

moment: Days before Lorne Green's death, Hamlett announced the

actor had died. "I guess we really scooped 'em on this story, didn't

we?"

Philosophy:

"...If listeners feel a little bit better and go to work smiling and

laughing, we've done our job," Baker said.

|

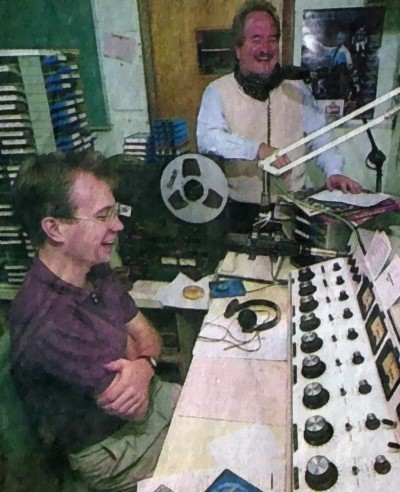

WMGB enlivened its music some but attracted

more attention by retooling its morning show March 16.

The morning disc jockeys, program director Pete Hamlett, 28, and Frank Baker,

37, are imports from Columbia, S.C. and call themselves "The Breakfast

Flakes."

Their off-the-wall humor and suggestive repartee with listeners is a mild form

of "shock radio," a popular approach in many large cities.

But even with that, Baker, who makes most of the off-color comments, would

stand out because of his Deep South accent.

The tacky joke of the day, he tells listeners, is that International Business

Machine Corp. is making a new typewriter called the presidential Selectric.

"It has no memuhry," he says in his speeded-up Jimmy Carter drawl, "and it has

no colon."

Off the air, he laughed about the joke, "I'm sick," he told Hamlett. "I'm

sick, sick."

Hamlett agreed.

"Cahmudy's tough," Baker said, grinning. "Cahmudy's tough, and we prewve it

ev'ry day."

The key to being competitive is aiming for a certain audience, general

managers say.

How each fares with listeners of different ages and men and women is reflected

in the ratings compiled by two services, Arbitron and Birch.

Those in the industry disagree on which service is more valid, but they do

agree on one thing: Birch ratings tend to favor stations with younger

listeners, while Arbitron favors those with older audiences.

Birch's summer ratings show that for all listeners, WFMI had the largest share

of listeners. Rounding out the top five were WKQQ, WVLK-FM, WLAP-FM and

WVLK-AM.

The Lexington market includes 15 stations. In Arbitron's spring book, the top

six stations overall were WLAP-FM, WVLK-FM, WFMI, WKQQ, WVLK-AM and WMGB.

The higher level of competition creates some additional pressure, disc jockeys

say.

|

|

|

Gary Green, "The G-Man"

Call letters:

WLAP-FM (94.5).

Target audience:

Ages 18 to 49; women.

Typical artists

played: Whitney Houston, Bruce Springsteen.

Green's favorite

artist: Boxcar Willie.

Memorable on-air

moment: Green made a prank phone call, telling a woman she would

have to reschedule her wedding because of a mix-up at the site she

planned for the reception. "Oh my God," the woman said, her panic

being broadcast across Central Kentucky. "What the hell am I going to

do?"

Philosophy:

"People are primarily listening for the music, and more you yak, the

less you play.'"

|

"There's a lot more competition here than in

other places the same size," Green said.

"There's one thing about this business. When you come into one station and

mention another station's call letters, it usually rings bells."

Green, a direct but friendly man with a boyish face, bristles at the mention

of competing stations.

"We're leading the market, and you get all these little, suburban stations

acting like they're doing so well," he said, sliding headphones over his ears.

Green does have kind words for one competitor: longtime friend Indy Jones,

program director and morning disc jockey at WFMI-FM in Winchester.

Jones starts spinning dance tunes for this station's young listeners while the

streets of Winchester are still dark and the Clark County courthouse glows a

ghostly white.

"He's one tough jock," Green said, as the phone in the booth rang.

A young caller made a request.

"Sorry," Green said into the phone. "We don't play Motley Crue here."

"A lot of females listen to this station," he said after hanging up, "and they

wouldn't like Motley Crue much."

"That kid who called is probably 13 or 14 years old and wears black T-shirts."

Not exactly WLAP-FM's target audience.

"The targeted audience is something more and more advertisers are looking

for," said Brown, the general manager of WMGB.

Radio has made a comeback since stations began targeting their audience more,

Brown said.

"I think what has happened with radio (is) it's a lifestyle medium now," Brown

said. "You can have access to it almost anywhere you go. And young Americans

are tremendously active now."

|

|

Eric Stevens

Call letters:

WLAP-AM (630).

Target audience:

Ages 25 to 49 with emphasis on 35 and older.

Typical artists

played: Lionel Richie, Huey Lewis & The News and Marvin Gaye.

Stevens' favorite

artist: Steve Winwood.

Memorable on-air

moment: Once, at another station, while Stevens was telling

listeners about a flood in which people died, a co-worker laid on his

stomach on a table and made paddling motions with his arms. Stevens

had to struggle to keep from laughing during the somber newscasts --

and was not entirely successful.

Philosophy: "The

greatest compliment anybody can pay me is for them to say, 'Hey, he's

my friend on the radio.'"

|

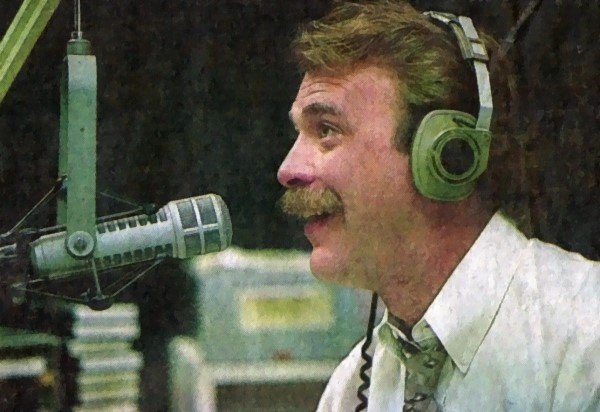

That includes disc jockeys, said Eric

Stevens, WLAP-AM's morning man.

"You gotta be active," said Stevens, who WLAP newsman Craig Cheatham

good-naturedly calls "GQ Johnny Fever."

Fever was the ragged morning disc jockey on the now-syndicated television

series "WKRP in Cincinnati."

Stevens is an amiable, outgoing man who wears his hair swept back, his shirts

crisp and his ties straight.

He stays active doing wedding receptions, parties and picnics to supplement

his income.

"It's a high-risk, low-profit field," he said.

Especially in the mornings. On a recent day, the clock said it soon would be

10 a.m., and the booth around Stevens was filled with smoke.

He took a drag from still another cigarette and chased the nicotine with

coffee.

"Boy, I sit here and chain-smoke and drink coffee like crazy," he said,

smiling. "This show's hazardous to my health, I tell you."

Stevens sighed and looked up at the clock on the wall. "One more contest to

go," he said.

Moments later, the clock said 10.

The phone was still, another morning was over, and Stevens plugged in one last

song:

"Happy trails to you,

"Until we meet again.

"Happy Trails to you,

"Keep smilin' until then…"

|